Nell Catchpole

APR25: Creative Outputs

Please listen with headphones in full screen mode

PhD Project Summary, March 2024

This creative practice research explores the socio-ecology of Teesside at a time of environmental degradation, socio-economic disadvantage, and industrial ‘development’ through listening/sounding with its human and more-than-human inhabitants.

The project investigates how "ritualised" sound-making practice draws local participants into closer relationship with their lived environment, exploring participatory ecological art’s potential for affect/effect through collective “intensities of listening” and sonic actions.

Interdisciplinary, and informed by anthropological methods, this project addresses key critiques of environmental and participatory art. It will enrich the emergent field of 'ecological sound art' by critically examining the nexus of ecological listening/sounding, social justice, and participatory art.

Transported

Most Creative Station programme. Awarded Artist Residency.

September 2024 – May 2025. (30k)

Transported was an installation at Middlesbrough Train Station which I devised and created with participation from the station staff, local community groups, a school and the general public. An ultrasonic speaker was positioned on each of the two platforms, a sensor triggering a randomly selected track to play when someone stood underneath. The sonic content was many (over 40) short spoken-word pieces, some with accompanying sound/music. Each piece was a reflection, poem, story or observation created and spoken by participants in response to a (facilitated) experience at the station. In addition, media players and headphones were set into the wall of the 1950’s waiting room playing interviews with the station staff. Specially designed posters on the station concourse included ‘freephone’ numbers that passengers could either leave or listen to messages. I also collaborated with local artists to design and fabricate golden ear sculptures and various elements of graphic design to draw people to the sound installations.

Whilst this was a substantial commission, I see this work as complementary, rather than core to, my PhD research. It has particularly helped me develop my practice as research methodology in the following ways:

· Developing modes of participation and co-creation, exploring ethical principles in and through practice.

· Devising ways to include creative indeterminacy within a funded project with set structures, agendas and lines of accountability.

· Critical reflection around the notion of ‘socio-ecology’ in the context of Teesside/Tees Valley.

· Developing skills in ethnographic observation. Documenting the dynamics between myself; my artistic ideas/plans/ideals; the actual process; and the different forms of engagement and interaction with specific participants and the local public.

· Sound design and ‘composition’ in response to/interacting with site and social context. Developing skills in forms of audio technology and production that are new to me.

Transported

Full track list for the whole project.

Selected Tracks

Gongs of Teesside

Gongs of Teesside is a project I conceived and have then raised funding for. This year has seen three connected phases of the project either completed or begun. Each has been funded separately. The phases are described below.

I see this project as a core part of my PhD submission, with at least two further practical phases that I would like to add.

With collaborator sociologist, Sarah Irwin, the fundraising process has been a way to develop and articulate complementary areas of research for the GoT project. In her case, this is around inter-/cross-generational perspectives on place, past and future with a focus on ‘felt relevancies’ of de-industrialisation and re-development in the area. My own evolving areas of interest are outlined at the bottom of the page. We share a motivation to explore and contribute to discourse on Climate Justice, particularly on listening to and amplifying under-represented voices and perspectives.

Across all phases of the project, the sounding of the gongs generates processes of listening, dialogue and inter-relationship to place and landscape.

Gongs of Teesside: Forging Collaborations

Awarded Sapling Fund, Leeds University.

Collaboration with Prof. Sarah Irwin.

January 2025 – May 2025. (5k)

This phase is nearing completion and has involved ongoing collaboration with two local blacksmiths, Peat Oberon and Matthew Snape, with advice from Filipe Alves, a Portuguese gong maker based in Wales. Together we have learned and developed a method for fabricating gongs made of steel. This work has taken place at Preston Park Forge over the past year, with support from Preston Park Museum. The process has been an extended dialogue – between the blacksmiths, me, the steel, and the instrument design. I invited ‘Preston Park Young Producers’ to document the latter stages of the process, and this was facilitated by myself, Sarah Irwin and collaborator Rachel Deakin, a local photographer and videographer. A further dimension emerged out of this which was a collaboration with Redcar College welding tutors and students. We invited the welding students to the forge to meet blacksmith, Peat Oberon with a follow-up exchange visit to show Peat around the welding facilities at the College. Alongside this, we have invited the students to create designs to be laser cut in steel and mounted on the gong stands. The designs are representations of places/themes they see being of local significance. Again, this process is offering a space through which to hear the perspectives of this younger generation on place, the past and their hopes and plans for the future.

As a final stage of this phase, we held a public participatory event co-hosted with the Young Producers where the public could identify and mark a place on a map of Tees Valley where they would sound the gongs, adding a note to explain its significance to them. They were also invited to sound the gongs.

The Young Producers’ documentation of the gong making will be included in a co-curated exhibition in the Autumn.

Gongs of Teesside: Sounds of Steel

Awarded Historic England ‘Everyday Heritage’ funding (20k). Collaboration with Prof. Sarah Irwin. February 2025 – October 2025.

This phase of Gongs of Teesside involves developing collaborative relationships with members of communities associated with Redcar and the Redcar Steelworks, and Skinningrove in East Cleveland. In each case, the idea is to co-create a gong sounding event in a place of significance chosen by the participants. Young people will be invited to document the events as a means of engaging them and also to explore their perspective on the process.

The locales were chosen following scoping meetings with several local people introduced to me through my local network, and then was further narrowed down by the criteria of the Historic England fund (coastal communities). Themes and issues emerged or were reinforced from these conversations, including the rapid changes of experience and outlook from one generation to the next; controversies around Teesport/Teesworks developments (and its environmental impact); the strong feelings about the demise of the steel industry and loss of jobs and community; and concerns about the future.

Since those initial meetings, and with funding in place, I have been building connections and having conversations with individuals and groups towards the creation of the sounding events. The process is quite different for each location.

Redcar Blast Furnace site, on Teesworks:

The site of the blast furnace was suggested as a sounding location by local colleague, Liz MacIver. The furnace was closed quite suddenly in 2015 with the loss of 3000 jobs. It has been demolished in the last couple of years, but symbolically, the iron ore left in the furnace to cool formed a solid mass (known as a ‘bear’) which the developers have yet to be able to remove. It stands on the south bank of the River Tees in a wasteland that is being prepared for developers, including a process of land ‘remediation’. Teesworks itself is a vast development of 4,500 acres, claiming to be the largest brownfield site in Europe. Large-scale developments, which are variously described as ‘sustainable’ or ‘net zero’ are either being built or are in (or out) of the planning stages. Teesworks as an organisation and the (closely linked) Tees Valley Combined Authority and its Mayor, Ben Houchen, proclaim that thousands of new jobs will be created. Local people I have spoken to over the last year or so have differing feelings about the project, but much of it is negative or wary at best.

Liz MacIver’s first job at age 18 was sorting scrap steel at the steelworks. In an interview, she described how her Grandad used to walk to work from Carlin How in East Cleveland to the steelworks. She progressed into working in Health and Safety, and from this noticed the environmental impact of the industry. Following a series of different and more independent ventures and roles, she now leads the Tees Valley Nature Partnership (responsible for reporting on the Local Nature Recovery Strategy). I have invited her to co-create the Gong Sounding event at Teesworks with me, including deciding who to invite, how to site and play the gongs, and what else to include in the event. She remembers standing on the hills with a crowd on the night the steel furnace was closed and feels there ‘hasn’t been the right opportunity to grieve’. On the other hand, she is keen to find ways to access and make use of resources from wealthy companies to fund nature conservation projects in the local area and is connected to most local nature organisations. Her current focus is on setting up a working group of young people as part of the Nature Partnership. The combination of Liz’s local knowledge, personal history, passion for place and environmentalism is revealing new understanding for me, as well as rich inter-connections across places, people and organisations.

A recent site visit and ‘recce’ saw a team of 7 of us at Teesworks, including Liz, Prof. Sarah Irwin, Peat Oberon, George (young sound artist and engineer, and son of Liz’s best friend) and Mavis (Preston Park Young Producer and photographer). We were hosted by Neil Young, Teesside Freeport Skills & Workforce Development Manager, who drove us round the site in a mini bus (and with whom I have been in discussion with for several months).

The site visit in blazing sun had the quality of a strange dream, full of (as yet) unprocessed meanings, metaphors and complexities. As with the rest of this project, I see the entire process as a co-creative, emergent one in which listening and creativity are ‘in play’ as a continuum. The process towards making a gong sounding event is generating constant micro-moments of interest, connection, adaptation and new ideas.

During the site visit, Liz picked up on a newly created water course which she believes runs from the site into an SSSI (Site of Special Scientific Interest). Liz has subsequently said she doesn’t think this is known about by the relevant local nature conservation organisations. This is unconfirmed, but it has potential to be an interesting moment of ‘effect’ in the project - where an unplanned but potentially significant environmental issue has come to light as a result of the project and participants. This connects to conversations with my supervisor, Prof. Nanette De Jong about artistic research practice as intervention.

The event date is set for June 24th, midsummers day.

I am thinking about the curation of the event and how each element will affect its meaning and impact:

o Gathering point (Does it have to be the very corporate conference room at the entrance of Teesworks which is designed to impress?)

o Who hosts and introduces the event, what is said

o When the gongs are introduced (eg at the gathering point, then guests help bring them, or are they waiting at the event site?)

o The exact location on site for the gong sounding - its meanings/associations with the past, present and future. (Also weather dependent)

o The sound of the gongs in relation to the site (at the recce, I noticed how the gongs suddenly look and sound smaller in relation to the scale of the site and its machinery)

o Who plays the gongs, whether this is pre-rehearsed, where people stand to hear them, how long they are played (eg is it a performance by ‘performers’, or are all guests invited to play the gongs in their own time?)

o If and when people share their thoughts and experiences about the sounding – who this is for, how it is structured, whether it is documented and how this all affects peoples’ experience as well as what they say to each other.

o What the unintended outcomes of the process might be and staying open to these. For example, at the recce, Liz was interested in networking with Neil; Peat was fascinated with the Teesworks site; George was posting shots on Instagram. The sounding of the gongs may prove to be as much a vehicle for generating other outcomes, as it is a potent moment in itself.

o My interest was piqued in the reference to soil remediation – the site is mostly flattened, barren, dusty land. What does this process involve and how does it tie into the ideas behind GoT?

Skinningrove Harbour seen from Carlin How

Skinningrove and Carlin How with Land of Iron, East Cleveland:

For this locale, we have been introduced to Land of Iron’s ‘community connector’, Nikki, who is a Skinningrove resident and clearly a lynchpin in the community. I am at the early stages of meeting community groups and communicating the idea of the gongs. It had already been made clear to me that this is a tight-knit and somewhat insular town which is geographically isolated, having been at the heart of iron mining in the past. We were given the impression that there is quite a lot of politics between Skinningrove and Carlin How, the neighbouring village, with memberships of different families and community groups being contested. As with Redcar, there is a reduced amount of industry, including TATA steel works (closed) and British Steel (still open) at Carlin How.

Nikki talked a lot when we met her and shared her personal story about being one of many grandmothers bringing up their grandchildren because their own children ‘made bad choices’. She took us up on the cliffs overlooking the town as she thought this might be a good place to sound the gongs. Like Liz, she had also done a stint of work in the old steel works that stand here. She then moved into social work.

She has since been very difficult to pin down – something which she seems to be known for, despite being employed by Land of Iron. This sense of the town, and the townsfolk, being a ‘rule unto themselves’ is prevalent.

The Carlin How Keep Fit group (aged 60 – 90+) talked about how community has changed – how families from outside get housed because it’s so cheap; how people don’t look after the neighbourhoods anymore; and the same people show up when there’s free food but don’t contribute. There was a real hesitancy from the group that they didn’t want to be seen to be the only ones contributing ideas about the gong sounding. (E.g. ‘What about the men’s perspective?’) And they were anxious that I was expecting/needing large numbers of participants. Equally, there was appreciation of the village Primary School and thoughts about getting them involved. And talk of thinking about the gong sounding as a ‘healing’ process.

My next steps are to continue visiting and re-visiting groups who have expressed interest, building relationships. The gong is a strong talking point, or ‘way in’, and showing photos of the gongs being made instantly seems to give people a more direct sense of contact with them and interest in the project.

In all the above, the ethics and politics of these interactions are high on my mind. The process of ‘co-creation’ (and especially the degree of ‘co’) has many layers of information and meaning to it.

What is the role of the gongs in terms of the affect/effect of the project?

Does the fact they are made locally of steel give them more meaning to communities? How?

What are the cultural meanings or associations with gongs for participants, including ideas of the ceremonial/ritual?

Does their accessibility help to create moments of meaningful shared experience?

Does the quality of their sound take people out of their everyday ways of perceiving, and what emerges from this?

Do the gongs are simply a reason to meet, interact and be with places and people, OR do they mediate and affect the listeners’ experiences in specific ways?

What meetings and conversations are needed to develop a sense of shared interest and engagement with the project?

Gongs of Teesside: Unbeaten Valley

Commission from MIMA (Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art) for ‘Bottle of Notes’ Exhibition. With Rachel Deakin. November 2024 – October 2025.

This project forms an interesting parallel with the above phases of GoT in that each sounding is a more personal, contingent response to each place/time. It is a clear extension of my existing landscape practice, with the same method of atuning to the place, finding an exact spot that I am drawn to, and sound-making in response to its sonic ecology.

To date, we have completed and installed 3 out of 6 monthly gong soundings. This process will be completed in August.

One reflection is how this process allows for site-specific, complex documentary narratives to emerge – rather than the propensity towards sweeping meta-narratives of de-industrialisation, industrial heritage, class, deprivation, etc that both funders and participants might tend towards on the other projects. Does this allow the place to ‘speak for itself’? And what does that contribute (to its communities, to Climate Justice discourse)?

The different collaborative methods for selecting places for gong soundings is also of note. So far: the invitation to the public to put a sticker on the map; the more in-depth discussions with local individuals and community groups; and the dialogues with different academics - as with ‘Unbeaten Valley’. These call on different kinds of knowledges, interactions and understanding. I intend to add a further phase of activity next year of spontaneous gong soundings in unlikely places. I see this as being more radical because they aren’t well-known points of interest or cultural places and because I would do this without the constraints/agenda of any funding. It might lead to unplanned, unexpected dialogues and activity that would otherwise never have been considered.

Unbeaten Valley

Soundings

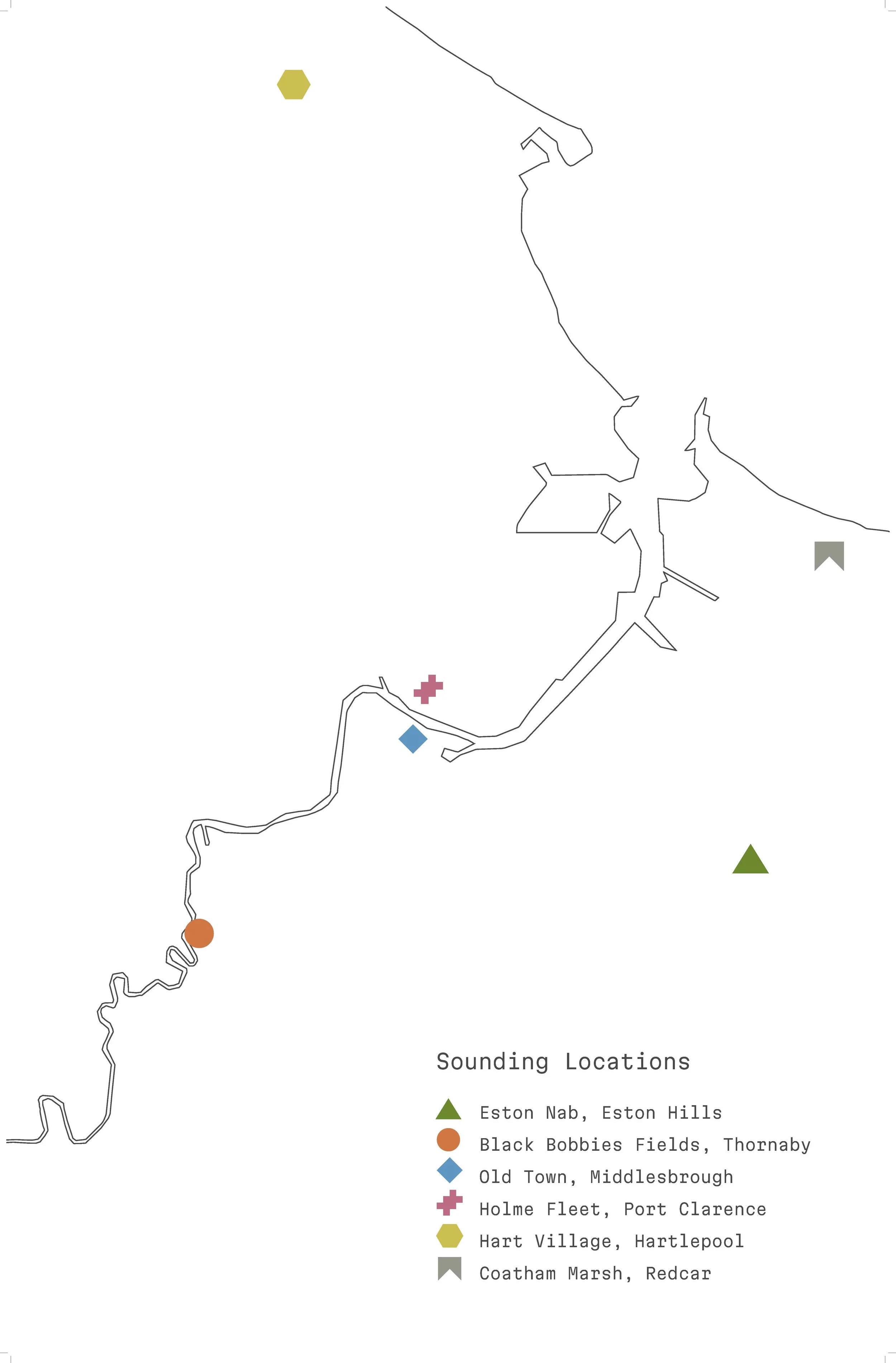

I visit a different, pre-decided location each month and do a gong sounding. February - Eston Nab, March - Black Bobbies Fields, April - Boro Old Town are completed and the resulting sound pieces and photos are installed in the MIMA exhibition.